|

With all of this extra unwanted screen time, Irvington resident and Physical Therapist, Karen Gstalder-Dring has suggestions that will benefit our children's (and our) bodies considering the variety of the positioning, the chair/desk and the environment. Is the chair fitted to your child's size? What are the best ergonomics for the chair/computer screen on the desk? How can you have your child move a bit in their "home classroom? Read on to learn what Karen suggests.

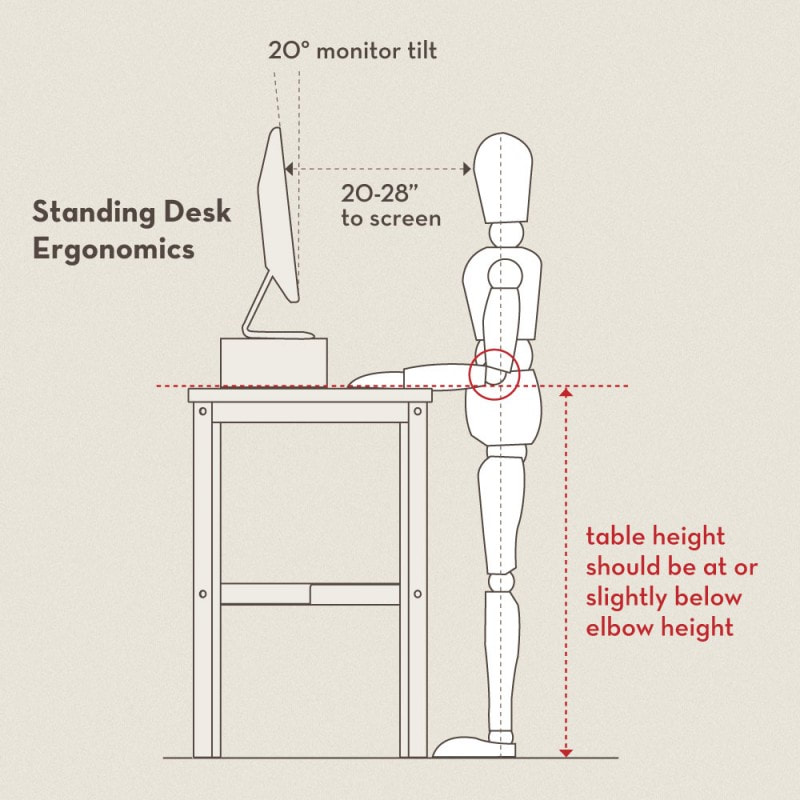

Karen Gstalder-Dring, MS PT So our kids in K-12 are being asked to sit and attend to a screen for a minimum of 6 hours/day. There are many exercises that we can all do to ward off the deleterious effects of sitting for a prolonged time but that is for another discussion. Let’s instead talk about variety: variety of the positioning, the chair/desk, and the setting. Positioning: Ideally a chair is fitted for your size. You want your feet comfortably on the floor, your pelvis slightly higher than your knees. If your seat cannot be adjusted to slightly tilt downward, aiding in a neutral pelvis, consider placing a towel fold just under the back third of your child’s ‘Sits bones’. If the seat is too deep considering bringing the back of the chair to the child with a pillow against the back rest. Most arm rests are set too wide to use while typing. Alternately, consider resting a firm pillow on your lap so that your elbows can be supported more directly in line with your shoulder joint. The chair/desk: Sitting at a desk with a Chromebook or laptop is not ideal. For the best ergonomics, you want your monitor to be at eye level, with your neck and head in neutral (not looking downward), and your wrists resting on the keyboard slightly lower than your elbows. If you can raise your monitor to bring it to eye level by putting your laptop on a box or stack of books, you may want to use a separate keyboard. So yes to a standing desk, but you don’t need to use it for the entire 6 hours and it doesn’t have to be an official expensive one. Look around the room. Is there a dresser? A book shelf? Do you have a few game boards or a plastic storage box to make the proper proportions? Make it as easy a transition as possible or it won’t be used as an option between/within a class. The setting: Even the elementary kids are accustomed to getting up and moving from the classroom for specials, lunch and recess. Most of us are all making due with multiple family members getting work done under one roof. Try to create variety within the child’s ‘home classroom’. A standing desk is an example, but so are a physioball, and a kneeling chair. No one is going to want to work 6 hours straight in any one position. Our bodies need a variety of pressure changes and support. If you are fortunate enough to have several work stations in your home, consider suggesting your child rotate around at various times of day. If you have kids of similar sizes and proportions, suggest they swap rooms half way through the day. We will get through this. All the above will help make it happen a bit more efficiently.

2 Comments

By Francis O'Shea

I have a problem with my phone. When the phone doctors looked at my screen time stats, they had to change the addiction scale so it went to eleven. So, over these holidays I strove to live a more phone smart lifestyle. I used all the suggestions from HeadsUp Rivertowns' awesome January Initiative. These ran the gamut from loading apps on my phone that track my activity and reward phone down time, to simply taking the time to reach out to my friends and loved ones by actually calling them. And after a week of mindful phone use I’m proud to say they made a big difference, and a few strategies really stood out. But before getting into which techniques worked best, let me tell you why I decided to take this challenge on in the first place. When I want to distract myself I look at the news. And I’m not sure if you follow the news these days, but this is just a horrible idea unless you actually like to be anxious and depressed. And while I've always had a hard time sleeping, recently the constant background flow of distressing information has taken its toll when I try to unwind. On top of that I use (or used) my phone as an alarm clock, and because I have Kindle loaded on my home screen it comes to bed with me at night. In the morning my first move when I wake up is to pick up my phone, and all too often to flick through my apps to see who emailed me overnight and what other notifications I’ve received. And even when I’m not trying to sleep, more and more I’ve found my phone creeping into my quality time at home. Over the dinner table, when my daughters want to play or tell me about their days, or when I would usually be practicing guitar or reading, I’ve found myself mindlessly scrolling through social media or the news. So, the first step for me was mindfulness: I simply noted whenever I was picking up my phone in the days leading up to my big week, and once the challenge started I consciously avoided those behaviors. As it turned out, staying away from the news over the holidays came pretty easily. I suppose I was full of holiday spirit. Mostly I found myself over checking my email because I couldn’t believe my last days at of work before the break could be so low stress! Going forward, scheduling email check ins 3-4 times per day would help with this, I’ve even thought about making an autoreply on my work account setting the expectation that I won’t reply immediately to emails. But I haven’t bitten the bullet yet. There are a slew of features on the iPhone that help with scheduling phone time: geo-fencing your reminders, pre-scheduled Do Not Disturb, and aftermarket apps. There is a circularity to this, using an app on your phone to use your phone less. But I will learn more about these going forward. After a week, there was one technique that popped out above the rest: giving my phone a bed and a bedtime. For me this came to combine several of the challenges: no screens before bed, charging phones outside the bedroom, use a traditional alarm clock, and don't look at your phone for 30 mins after wake up. Separating from my phone when I walked in the door became a great way to decompress and focus on quality time with my kids after work. Some folks I’ve spoken to actually build a bed for their phones. My phone can sleep on the shelf with no cover, thank you very much it gets enough out of me during the day. But the phone goes in the same spot each night when I walk in the door and stays there until the AM. I will usually go and unplug the phone before bed and make sure no one has actually called me or texted about an emergency. But even picking it up after 8pm is a no no. And as it turns out, I missed almost nothing that matters in my life! This practice was really a game changer. In retrospect, the hardest thing for me was not looking at my phone in the car. I didn’t even notice how often this was a problem. It’s embarrassing to say that even during my week of phone mindfulness, I actually posted/emailed while driving with my kids in the back of the car! As for texts I’m not sure if I can honestly count. Usually it was in response to a text or notification, so I tried turning on Do Not Disturb before I took the wheel. But that was hard to do consistently. Going forward I am going to experiment. I’ve heard there are ways to make it so my phone won’t let me use it when moving at a certain speed. But then how will people in 10533 know what I think about the new drive up mail drop?? The horror. This was the hardest part for me, realizing that I did this very dangerous thing out of habit. I'm sharing with you if you’re like me you will know you’re not alone. Oh and now I just keep my phone out of reach when behind the wheel. But for all that I hate about my phone, I have to say she came through over the holidays. Whether it was recording my daughters first Christmas in our new house with ease, FaceTiming with faraway family members or changing that annoying Christmas song before it bore a hole in my head, during my mindfully phoneLESS (read not phone free)week, my phone was blessedly not much of a source of distraction. Well, ok I may have spent a little too much time posing for that perfect iG post, but I can put that up to my own vanity. As some of us have said, it's an easy way out to blame phones and apps for all our problems. It really begins with our own behaviors. Epilogue – Sadly, after my phone smart week I have found myself backsliding. And in retrospect the holidays may not have been the best time to be more mindful. There were lots of great reasons to have my phone with me that brought joy to our family time. These phones really are amazing tools. I plan to do this again during a normal work week to get a sense of what works during "real life" and report back to the group. Stay tuned! This holiday season (or any time!), consider these amazing smartphone alternatives for kids. Tracphone Allcatel Flip -Calls & Text -Calendar App & Camera -$20 device -$40 for 200 minutes -Available at Walmart / Target Twigby.com -Complete parental control -Monitoring tools -Many phone choices -$20 device / $9 per month RLAY -No screen -includes GPS Tracker -$25 device -$10 per month available at Target or Amazon KidsConnect -$90 device / $15 per month -Pre-Program 3 numbers -Available at Amazon SportsCarModel -Flip Phone -$30 device -Monthly service via T-Mobile VTech Kidi Buzz -Send Text and Voice messages -Pre-Approved list of contacts -Learning Games -Kid-Safe Browser -$70 device -no monthly service needed GabbWireless.com -Safe cell-phone network -Designed for tweens -Looks like a smart-phone -No internet / no games / no social media -$99 device -$20 per month unlimited talk & text Attachments area The True Story of One Kid, Five Phones, and Why Waiting Until 8th Would Have Been SO Much Cheaper9/26/2019 By Delina Codey-Barrachin

The First Phone February, 2016. “I need a phone,” the begging began. “I really, really need one.” I sighed. “Didn’t we just have this conversation this morning? And yesterday? And the day before? Do you have some new piece of compelling evidence to enhance your case?” “I need it,” my son said, “because I am the only one in fifth grade without a phone.” “R doesn’t have a phone,” I pointed out. He shrugged, his best friend’s phoneless state clearly irrelevant. “Everyone in my class has one.” “You’re not really friends with the other kids in your class,” I pointed out. “Why do you care that they have phones?” “Because they all talk about things and I don’t know what they’re talking about.” “Like?” “They text each other,” he said. “They have a group chat for our class and they plan things and leave me out. They play games, and they talk about them. They do all kinds of things! We don’t even have a gaming system! I don’t have a laptop! I don’t have anything, and it’s not fair.” He paused. “And besides, even though R doesn’t have a phone, he has an ipad and a wii.” True points. “I’ll talk to your dad,” I said. “We’ll see.” We had promised T that we’d get him a phone when he started sixth grade, as most of our friends had done with their kids. Sixth grade, the beginning of middle school, seemed like a reasonable time, but we had noticed more and more fifth graders carrying phones on playdates and in sports carpools. “I like to know I can get in touch with him,” a parent said. “And he can call me if he needs me.” “I can’t believe you let T walk to school without a phone,” another parent told me, her voice barely disguising her horror. “What if something happens?” Like what? I wanted to ask. So he can call me right before he gets kidnapped? He was more likely to get hit by a car while texting. But in February, 2016, when T was ten years old, we caved to the begging and got him a refurbished iPhone 5. It was close enough to sixth grade, we rationalized. And he wasn’t having the best year with the kids in his class. If he was getting left out and made fun of for not having a phone, maybe this would help him fit it. Right? T was thrilled. We went over our rules and expectations, wrote everything down and made sure he understood. The next morning he walked the mile to school as he did every day, but this time with a phone in his backpack. He felt cool. We were proud. The future looked bright and full of communication options. Everyone was happy. At 3:40 that afternoon, he pushed through the door and threw his backpack on the floor. “Y said I should have gotten a 6! He said 5s were stupid phones.” He stared at me, betrayal in his eyes. “Why didn’t you get me a 6? This IS a stupid phone. It’s, like, someone else’s old phone. It’s not even new.” I took a deep breath, holding back the lecture on being grateful that he was a Westchester ten year old with an iphone instead of a homeless child, or a refugee on a raft. “Did Y tell you all that?” I asked. “Because this morning, you liked your phone.” “I hate him,” T said. “And I hate my phone, too.” The first time I encountered Y, at a birthday party at the local pool the previous summer, he was organizing all the other kids at the party to hide from my son. “Where’s T?” I heard him say. “Let’s run up by the tennis courts so he won’t be able to find us!” I wrote it off as sadly typical mean-kid-ness, but when T found out Y was in his class for fifth grade, he broke down into tears and told me a number of things Y had said and done to him in fourth grade that were beyond what I could ignore. I called the school, but they wouldn’t change either kids’ placement, and T entered the school year with dread. The school principal had called Y’s parents, and Y had been warned that his behavior needed to stop, but it hadn’t. “Don’t let someone you don’t even like have that kind of power over you,” I said. “Don’t let him wreck your happy feelings about your phone.” “I do like him,” T said. “Just not my phone.” I’m not the first person to realize that children, at times, act like very small crazy people. Y, as the most powerful kid in T’s world, was both hated and desired, and what he said was truth. Mothers, on the other hand, spoke vague, Charlie-Brown-cartoon-like nonsense. I gave up and started dinner. As the days went on, T discovered that his phone, stupid as it was, was useful for certain things. He could call me after school and beg for a ride home, claiming that his legs were too tired, his backpack too heavy, the hill much bigger than it had ever been before. He could stop on the way home from school and play video games without me knowing. And when Y told him to sign up for a YouTube channel, for Facebook, for LinkedIn (super useful for a 5th grader), T went ahead and created profiles for himself all over the Internet. Y continued to insult T’s iphone 5, and we started seeing T tossing his phone like a baseball, chewing on it like a puppy. “If you can’t treat your phone carefully, we’ll take it away,” we said. “I’ll be careful,” T said. And then the screen cracked. “Look!” he announced triumphantly. “It’s broken.” “Good thing we have insurance,” I told him. “We can take it to the store, and you can pay the deductible with your allowance.” “But I told Y I was going to get a new phone by tomorrow!” he wailed. “I told him I was getting a 6!” “You thought if this phone broke, you’d get a 6?” I asked, incredulous. “Yes! Because this is an old phone. They don’t make 5s anymore. They only make 6s.” “True,” I told him. “At the Apple store. But this is from Verizon, and they refurbish 5s, just like yours. And they fix screens. Let’s go.” After he’d emptied his entire cookie-tin of savings, and spent a boring afternoon at an off-brand repair shop (because it turned out that the insurance I’d purchased with the phone did not cover cracked screens) we returned home with the same iphone 5 he’d started with. Good as an old refurbished phone could be- or so we thought. It turned out that whatever trauma T had inflicted on it to break the screen had also damaged it internally. As soon as he tried to use it, the letters started shaking, the screen locked up and then everything went black. “See?” T said, looking pleased. “It really IS broken.” “Good thing we have insurance,” I said. The Second Phone March, 2016 This time, the insurance did kick in, and we got a brand-new refurbished iphone 5. T stared at Phone#2 in disgust. “I don’t want it anymore,” he said. “This phone is just as stupid as the last one.” By this point, the entire phone experiment seemed unimaginably misguided, so I didn’t disagree. “You really don’t want it?” “Nope.” The phone had taken all his money, had given Y another thing to tease him about, and he didn’t like having to keep track of it. He shoved it in my desk drawer and we forgot about it. Three months later, he asked if he could have his phone back to use as a camera while playing golf with his dad. “Sure,” I said, and gave it to him. The two of them headed out, and I didn’t think about the phone until the next day, when I asked if he wanted to put it back in the drawer. “My phone?” he said, looking blank. “Yeah, your phone. Where is it?” T looked at his dad. “Umm,” my husband said. The phone had been left in a golf cart, and Find My iPhone located it on a street corner in Mamaroneck. “What should we do?” my husband asked, hoping that I wasn’t going to ask him to drive to Mamaroneck to confront the phone thief. “Make a police report and forget it,” I said. T agreed. We suspended the service and everyone was happy, especially the guy in Mamaroneck. The Third Phone February, 2018. T was in seventh grade, and just about everyone really did have a phone now. T was into photography, and not that into video games, and he was two years older, two years smarter, and hopefully, two years more responsible. The suspended contract I’d signed up for when he was in fifth grade was ending, and if we wanted to keep his phone number we needed to renew the agreement. We had an old iphone 6 in a drawer, which T said would be fine, “even though the camera on the iphone 8 is far superior.” “How about one of those life-boxes or whatever they’re called?” I suggested. “Totally indestructible?” “I hate those cases,” he said. “They’re all thick and weird and you can’t feel the screen right. I’ll just be careful. Really, really careful.” And he was careful, really, really careful, until we were hiking in Costa Rica 3 weeks later and he had his phone in the pocket of his shorts, and we all jumped into a rainforest pool. T was devastated. “That happens,” my husband said. “It could have been me. Let’s give him a second chance.” (Or a fourth…) The Fourth Phone April, 2018 We dried off the SIM card, put it into our other old iphone 6 and everyone was happy. The next thing to break wasn’t T’s phone. It was his backpack. The zipper was failing, but there was only a month or so left until the end of school. “Use a binder clip,” I told him. “Don’t bend over when you’re wearing the backpack.” “I bike to school,” he pointed out. “I have to bend over.” “Don’t bend over too much,” I said, and handed him another binder clip. And then one day he went over a curb on his bike, fell off onto the pavement and the phone bounced out of his broken-zippered backpack. It may or may not have been run over. He wasn’t clear. When he handed it to me, the phone had been peeled apart like two halves of a sandwich. “It was totally destroyed,” he explained. “Completely broken. So I wanted to see what was inside. I figured it didn’t matter since it was broken anyway.” “It matters!” I yelled, completely losing my cool. “Maybe it wasn’t that broken! Maybe it could have been fixed! Insurance, remember? But not now! Nobody can fix this thing!” I buried it in the trash, completely forgetting about electronics recycling. “I’m sorry,” he said. “It really did break.” “I think you have been hit by a phone curse,” I told him. “And I am never getting you another phone. Is that clear?” The Fifth Phone October, 2018. When T entered 8th grade, we were told that he needed a phone. Teachers were asking kids to use phones in class, to look up information, to check out books, to photo-submit homework. Even R, T’s best friend, now had a phone. “I will try this one more time,” I told him. “You are putting it in the most indestructible case on the market. If you take your phone out of the case EVER, I will Krazy-glue your phone inside the case and I will glue the case together.” He looked horrified. “Then I could never take it out!” “Exactly.” I held up the tube of Krazy-glue. “I am totally serious. “This is your last chance. If you break this phone, you can wait until college.” T looked suitably contrite. So we got a fifth phone. A brand-new iphone 8, from the Apple store, and a brand-new indestructible case. It’s ugly. It’s blue and clunky and the screen doesn’t feel the same. But one year later, it still works, even after he used it shortly after receiving it as a shield against a light saber (or maybe threw it at the friend with the light saber- we’ve heard conflicting stories). But it didn’t break. It’s much easier to control what he can and can’t do on the phone than it was four years ago, and we have all kinds of parental time limits and restrictions that he doesn’t like. What we like is that we can take the phone away when he breaks rules, and he cares enough about losing the phone to try to correct his behavior. We also like going on vacation to places without good Internet access. When we read that an eco-resort on some distant shore or forbidding peak has no wifi or cell reception, we book it as fast as we can. Parenting in a society where everyone has smartphones isn’t easy. We have to figure out how to keep our kids away from them so they can do the important developmental work of playing, of getting dirty and being bored and riding bikes. But when even kindergarteners are using tablets at school, keeping our kids away from screens can seem impossible. Still, it’s important to resist and delay, to give kids crayons, to make up stories or play 20 questions instead of handing over a device. Eventually, though, we do have to teach kids to deal with screens. Whether it’s at 10 or 13 or 16, we can’t cut them off forever. Whenever we decide the time is right, we have to teach our kids to recognize the pull of their phones, the dangers and temptations, the brilliant and enticing world. My twelve-year-old daughter complained mightily when we decided to join the Wait Until 8th movement last year. Now, though, she’s decided she doesn’t even want a phone. Her best friend doesn’t have a phone, nor do two of her other best friends. Instead, they email each other from their laptops when they’re supposed to be doing homework. But when they’re walking home from school, they’re talking to each other and looking for cars, instead of walking while texting. When they’re hanging out together, they’re creating plays, or drawing, or swinging outside. But if a friend comes over who has a phone, every time I check on them the phone is out and the playing doesn’t happen. We can’t keep our kids away from technology, but we can educate and delay, and try to convince our kids’ friends’ parents to delay along with us. And when we do get our kids phones, we can glue them into waterproof, crash-proof cases and hope that they don’t use them as baseballs, chew toys, or shields against light sabers. Then again, maybe that’s the best use for them. By Josh Chang and Aliya Huprikar, Freshmen at Irvington High School

The other night, a group of us went out to celebrate a friend’s birthday. At dinner, we immediately found ourselves glued to our phones. We spoke for a couple of minutes about what we wanted to order, but everyone soon ended up scrolling through Instagram or playing a video game. After a few quiet moments, looking around the table, everyone’s head was down. “Guys,” one of the group said. Everyone’s head shot up. “Let’s get off our phones. Here.” We collected everyone’s phones, stacking them up at the end of the table, face down. “Let’s be engaged,” someone across the table said sarcastically. We all laughed, but there was some truth in that statement. Too often, we end up distracted by sudden buzzes in our pockets that allure us into the endlessly addicting digital world. By putting the phones out of arm’s reach, we stopped those distractions, and just like that, we started to live in the moment and have much more fun. Someone had brought a deck of cards, and we spent the rest of the meal playing games and eating burgers. It was an awesome evening that we all truly enjoyed, one that wasn’t dominated by devices. The phone rule was flexible: we could still text our parents to let them know what was happening, and if someone wanted to show something funny online, they could, but all the small, impulsive interactions were limited. Putting everyone’s phones together and to the side is an easy way to keep your head up during times like dinner that should be about face-to-face interaction. When you keep your phone in your pocket it’s too easy to just “glance” at a notification and get sucked into the digital world, rather than the real one. Keeping everyone’s phone in one place prevents this, and makes that “glance” a lot more public. Organizing an activity, like a card or board game, is a great idea because it’s a screen-free way of ensuring everyone is engaged. In the end, the most important part is that everybody has genuine fun and meaningful interactions with the people around them, something that is difficult if phones are in the picture. According to a recent article in Atlantic Magazine, parent’s screen time is hurting children.

According to the article “Occasional parental inattention is not catastrophic (and may even build resilience), but chronic distraction is another story. Smartphone use has been associated with a familiar sign of addiction: Distracted adults grow irritable when their phone use is interrupted; they not only miss emotional cues but actually misread them. A tuned-out parent may be quicker to anger than an engaged one, assuming that a child is trying to be manipulative when, in reality, she just wants attention. Short, deliberate separations can of course be harmless, even healthy, for parent and child alike (especially as children get older and require more independence). But that sort of separation is different from the inattention that occurs when a parent is with a child but communicating through his or her nonengagement that the child is less valuable than an email. A mother telling kids to go out and play, a father saying he needs to concentrate on a chore for the next half hour—these are entirely reasonable responses to the competing demands of adult life. What’s going on today, however, is the rise of unpredictable care, governed by the beeps and enticements of smartphones. We seem to have stumbled into the worst model of parenting imaginable—always present physically, thereby blocking children’s autonomy, yet only fitfully present emotionally.” Obviously we all want to be good parents to our children, but in the tech saturated world that we live in, this sometimes can be hard, especially when it is all so new, and no one is telling us what we can do. As a therapist in the Rivertowns, below are some tools I share with parents in my practice to help mitigate the above phenomenon, and be more present in their children’s lives: 1). Tell your children what you are doing on your phones. (Ie. I’m looking up a phone number, I’m writing an important work email, I’m reading the newspaper, I’m texting with Dad). Before smartphones existed, kids used to know what their parents were doing because they could see! They saw you reading the paper, or looking up a number. Now they just feel ignored, they feel that they are not a priority. 2). Don’t mindlessly scroll in front of your child! You are telling them that you care more about other people’s (often stranger’s lives), than you do about theirs. And you are setting a bad example for your kids, (that it’s okay to spend hours of your time staring mindlessly at a screen). 3). Don’t use your phone at the dinner table, when driving, when talking to people. Put your phone down and look your children in the eye when speaking to them. Model the importance of face to face communication and common courtesy. 4). Put your phone away at concerts, when out to dinner, at social gatherings etc. Model the importance of being in the moment, NOT being constantly distracted by your smartphone. 5). Don’t carry your phone in your hand everywhere you go. Put it in your purse or pocket when out and about and leave it in one place in your home such as the kitchen counter, even when you go upstairs (unless you are expecting an important work communication etc.). This shows your kids that being in the moment matters, the phone can wait! 6). If you feel comfortable with it, leave the phone in the car when you are out, tell your kids you don’t need it, you can always go to the car and get it if necessary! 6). Explain to your children that a smartphone is a tool, and should be used as such, not a toy for one’s entertainment. Hope these tips help. Look out for more helpful blog posts from HeadsUp Rivertowns in the near future! Yep. They're asking for it. If your house is anything like ours, then your kids are asking for smart phones. They'll tell you they NEED it, but beware. We adults can attest to our phone's addictive power.

Here are a few tips to get you through the holiday season:

Working as a therapist in private practice, I have become aware of the pervasive problem we have with kids and smartphone addiction. Teens tell me all the time that they are addicted to their phones and that they wish they weren’t. We have all heard about the latest science behind why we should be concerned about our kids and their smartphones, but we haven’t been given very many actual solutions for how to decrease the chance of addiction. In an effort to help both teens and parents, I have come up with some concrete things parents can do.

This blog post will deal with the #1 most important thing I believe parents can do, and that is to delay giving their child a smartphone. It’s easy to fall into the trap of believing that your child needs a smartphone (ie. “I need to be able to contact her and she’s too embarrassed use a flip phone”, or “he will be excluded/she will have no friends”, “he will be left out of important school or social events”, etc.) None of these things are true. First of all, when you are beginning to give your child more independence, start by getting a home phone (if you don’t already have one). This way if you leave your child home alone you can still reach her/she can reach you. (Home phones all have caller ID now so there is no need to worry that she will talk to strangers. Teach her not to answer the phone if she doesn’t know the number). Kids need to learn to actually speak to people on the telephone, this is an important life skill! I believe it’s also important to teach our children some independence when they are out in the world. When you are first allowing him out on his own, have him take safe routes, or only go to a friend’s house, or stay in town. If he needs to contact you teach him to go into a store and ask to use the phone behind the counter, or ask a woman with children (considered the safest stranger to ask for help), or borrow their friend’s phone! When you finally feel they need a phone, start with a dumb phone. There is no need for your child to have access to the internet or apps on their phone! In fact it is the ability to play video games, use social media and access the internet that in my opinion creates the worst addiction. You can figure out creative ways to let them have music or a camera. Record players are back in style! Get an ipod nano, give them a real camera! (You can also “dumb down” a smartphone, taking off internet or ability to use apps.) Teach them that if their friends tease them or make them feel bad that they don’t have a smartphone, then they aren’t good friends! Allow your child’s prefrontal cortex to develop before you give them a smartphone. The younger they are, the harder it is for them to regulate their smartphone use and the more likely they are to become addicted to it. Research has even proposed a correlation between smartphone addiction and substance addiction later in life. This is serious stuff. Remember, by delaying your child’s access to a smartphone, you are not being evil, you are being a good parent, who cares about your child’s brain and social emotional development! For more concrete ways on how to decrease your child’s screen addiction or even to raise your child without a smartphone (What?! Is this possible?? Yes it is!!), check out the website: Familiesmanagingmedia.com What if your child already has a smartphone? Don’t worry there are still lots of ways you can decrease their chance of addiction. Keep an eye out for future blog posts where I will be sharing lots more concrete tips! |

AuthorHeadsUp Rivertowns Archives

October 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed